12 | Unisons & Octaves

The most straightforward and most often overlooked way of arranging for big band is by using unisons and octaves. Very often, you’ll see lines being harmonised that just don’t need it. Sometimes, having a lot of players back up a single line is the way to go. Firstly, let’s discuss two important points of big band arranging:

Unisons add weight to a line.

Octaves add volume to a line.

Like orchestrating for any other ensemble, just because you add more instruments doesn’t mean it gets exponentially louder. Two saxes are not twice as loud as one. Nevertheless, adding octaves will help a line project, provided it doesn’t get too low where it could become muddy.

Unisons change the colour and weighting of a line. The good news is the horns in a big band generally all blend very well together in most of their range. (Just be careful of the extreme highs and lows of any instrument). This makes decisions to do with doubling lines pretty creative rather than technical.

There are broadly-speaking two types of timbre available to us: reeds and brass. We can keep everything just reed, just brass or mix them. I’ve also used the word ‘hybrid’ to show a mix of reed and brass timbres with a rhythm section instrument, and because the word ‘hybrid’ is really cool.

The sections that follow show the most common uses of unisons in big band writing.

UNISONS

These are combinations of instruments typically used for unisons, and the kind of sound they produce (i.e. reedy, brassy etc.):

Note that all of these unisons can be scaled up i.e. 2 Trombones could be 3 or 4 Trombones. (Although this would probably push the bass trombone too high or the Lead trombone too low). I’ve only included the most common unisons here. When you start getting to more than about 4 instruments, the sound starts to lose focus and tightness. As long as things are balanced and in good registers for each instrument, nearly any combination is possible in a big band.

OCTAVES

Octave writing in a big band is a bit of a different beast. A lot of the instruments operate within the same few octaves of one another which means it’s easy for lines to become muddy or to interfere with the rhythm section. Keep the span to 3 octaves or less, watching the lowest notes don’t go too low and it should be fine.

Saying that, octaves are ideal for when lines need to be clearly projected and cut through the band. You can also combine the unison colours above with various octaves to give the line weight and to help it project, as long as it doesn’t get too muddy. Here’s a table that will produce evenly balanced octaves - if there’s one player on the top line, have one on the bottom; if there’s two on the top, two on the bottom etc.

These are for even amounts of instruments. But what about when you want to use unison or octaves and you only want or have 3 players for instance:

If you have an uneven amount of players, doubling either the lower or higher line will result in a drastically different sound.

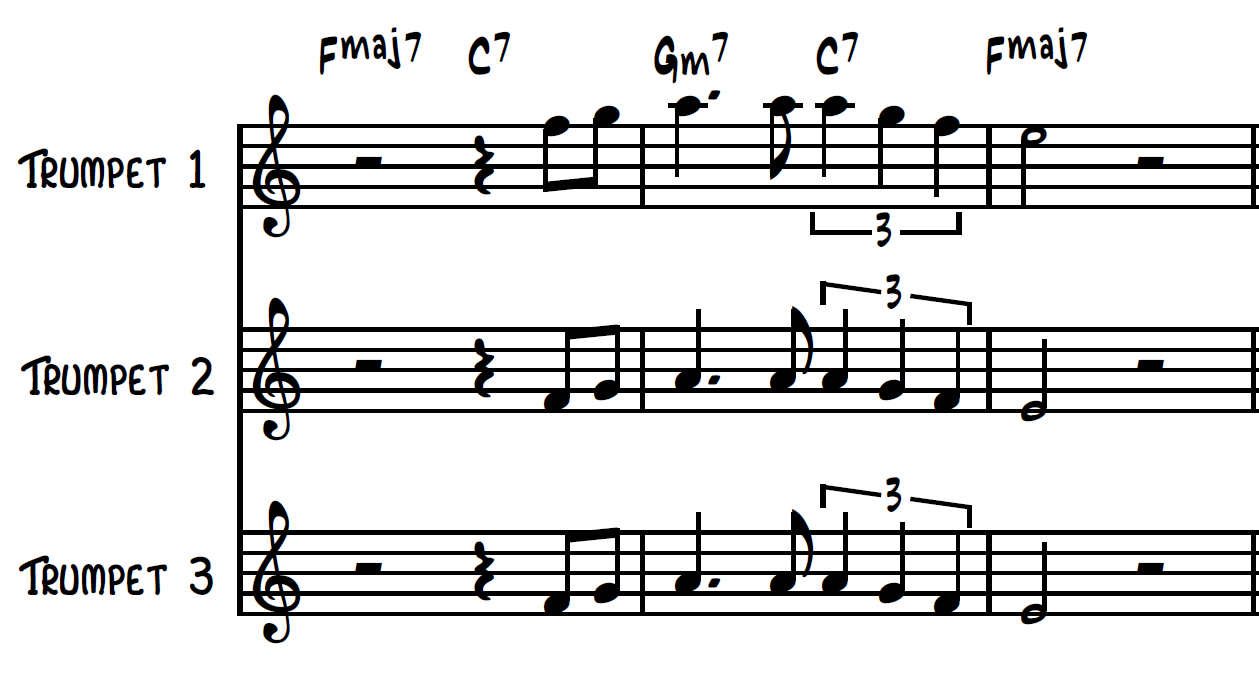

That means if you have three trumpets playing a line and they’re not in unison, they could be one of these two options:

Hear how they’re drastically different in brightness/darkness. When you have an even amount of players, you can balance it quite well by just distributing the octaves equally, but when you have an uneven amount of players like this, you should know how bright or dark you want the sound to be to decide who plays in which octave.

When you have an even amount of players, trumpets 1 & 2 the octave above trumpets 3 & 4 is a very common, balanced sound as shown in the table from before, so I’d usually go for this.

A general rule of thumb in unison/octave writing is to ensure each instrument is in a strong part of it’s range so the player can control and balance themselves against the other parts. A trombone or trumpet too high will have no choice but to play loudly and this limits your potential unison/octave voicing options.

2-PART WRITING

We can often use 3rds or 6ths to write in two parts. I’d recommend no more than two players on each part, so a total of four players. This way the melody will still sound clean and clear. This is very common in latin tunes and older charts. The same balance considerations as above apply.

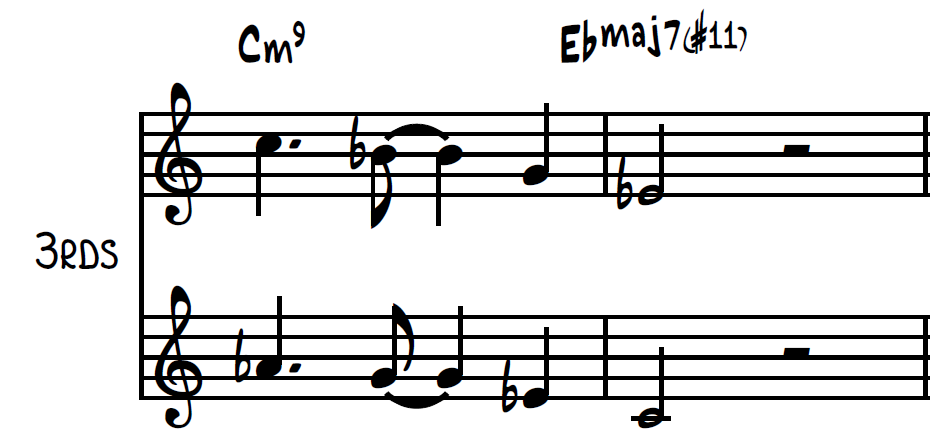

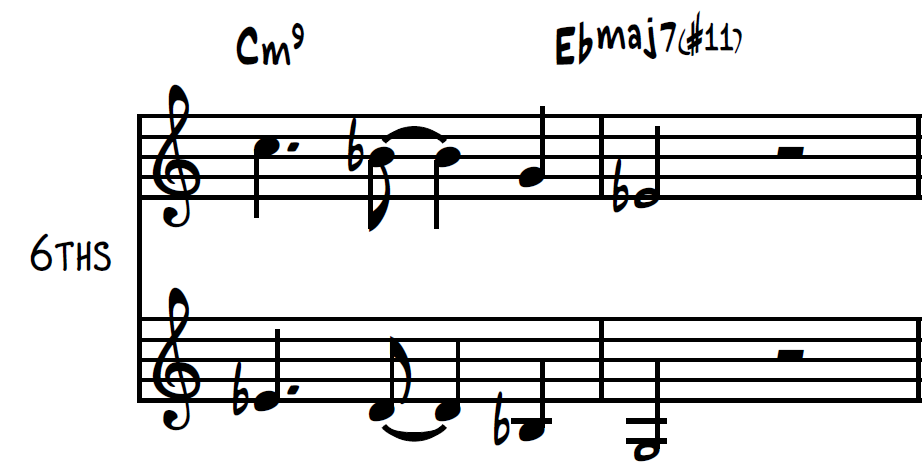

Here’s an example first in 3rds, then in 6ths. I could have put the 3rds or 6ths on top of the melody, but this way the melody remains the top line. The harmony (Cm9) isn’t too strictly adhered to, as thirds and sixths are generally strong enough to support themselves harmonically:

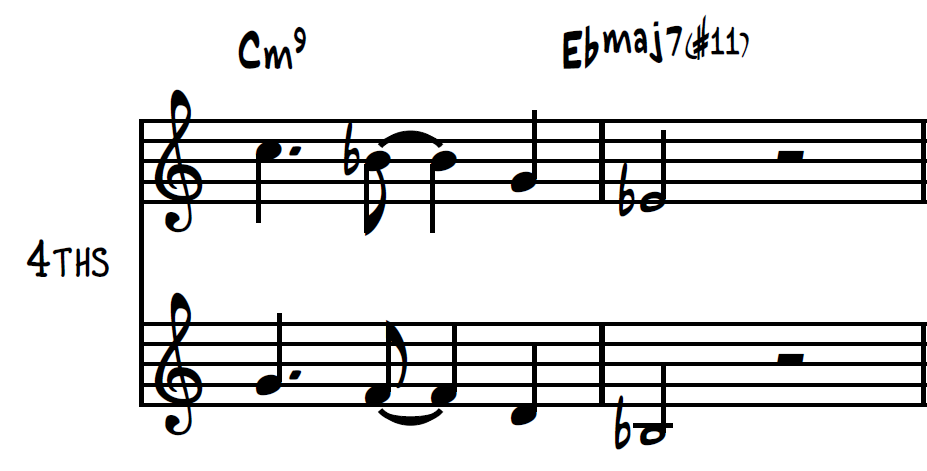

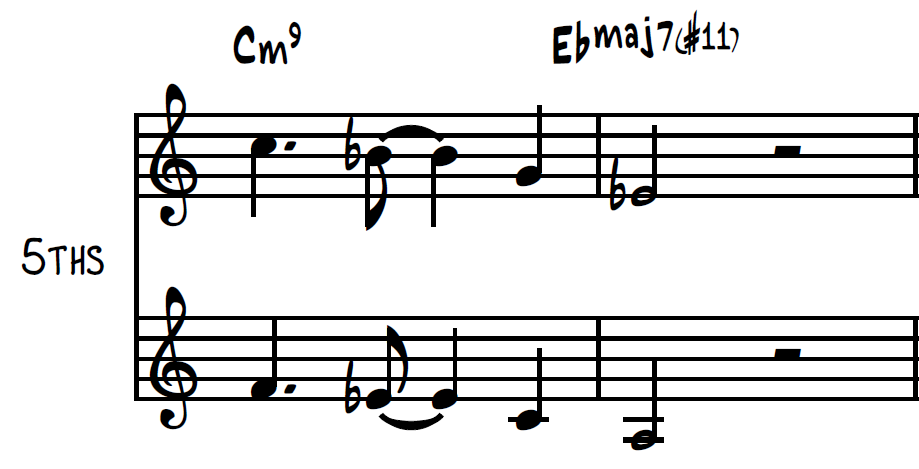

Fourths and fifths are also sometimes used, especially in modal jazz. This is a very specific sound that has to be treated carefully and not overdone for maximum effect. It’s very open and modern-sounding. Here’s the same line harmonised in 4ths and then in 5ths.

In usual circumstances, 2nds and 7ths shouldn’t be used to continuously harmonise a line for obvious reasons. For special effect though, it might be quite effect, especially if you brought different colour combinations into play. A very soft harmon muted trumpet playing parallel major 2nds significantly quieter than the melody can create a great effect. Think Bartok, Concerto for Orchestra, 2nd Mvt!