8 | Phrasing

This tip goes for all arranging really, not just big band writing. Pro players are incredibly sensitive to the articulations that you write and matching the phrasing exactly with any backing track. Starting together, ending notes together, using the same kind of vibrato, tone colours, power, groove, intonation - this sense of unity in a track is what makes it sound polished and professional. If what you’ve written accidentally contradicts the backing track or another part in the band in any of these aspects, there are going to be questions. It’s worth noting an important point:

Bad phrasing in the arrangement is the number one issue that causes wasted time in the studio with big bands.

I can’t stress this enough. Wasted time in an expensive studio or rehearsal is obviously not ideal.

Isn’t the general arrangement, voicing and balance more important though?

They’re important too (especially balance) but getting the phrasing wrong on the part is so much worse than bad arranging or voicings. Bad voicings can kind of be fixed by great players balancing themselves and playing in such a stylistic way that it kind of masks the writing. This happens all the time. But getting the phrasing wrong often leads to questions and is very obvious when not fixed, so takes the most time.

This advice only applies to parts you would usually want to be phrased and played together. So unison/octave lines, harmonies of the same line, parts using the same rhythms etc. Anything intentionally supposed to be phrased differently is fine to leave unmatched.

MATCHING THE PHRASING

Let’s imagine we booked a session bassist to lay down a 4-bar funk riff. There’s no bass part notated and they send back this audio:

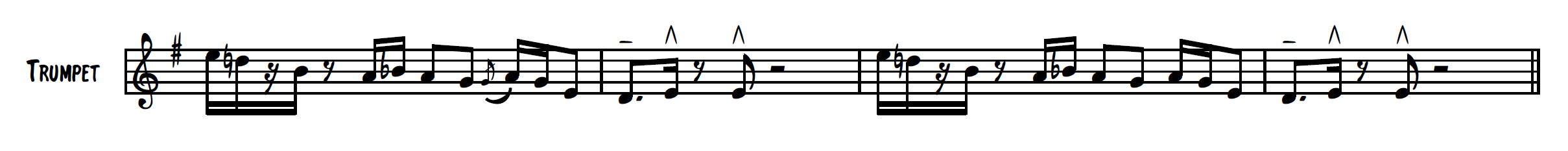

Now let’s imagine we wanted to add some horns to this. We start with the trumpet part:

There’s going to be problems. Because the trumpet part doesn’t match the bass part in terms of note lengths, articulations and phrasing, (and they’re definitely supposed to!), the trumpet player will ask the following questions when they see their part and hear the bass:

Should I be playing beat 1 of bar 2 short or long? (The bass is long, the trumpet is short)

Is the extra 8th note at the end of bar 2 supposed to be there? (The bass doesn’t play it.)

Should the rhythm in bar 3 match the bass? (There’s extra 16th notes in the trumpet at the end of the bar.)

Do you want me to end with the bass in the last bar? (The bass finishes a whole beat earlier than the trumpet is written)

You can see there are a lot of issues. In fact, let’s notate the bass part as it’s played and compare it to the trumpet part. Look how different they are when they should be playing the same thing:

Sometimes, the trumpet player would just fix it without saying anything, but when the part is this problematic, they might start to ask you questions. Each question takes away precious time from recording or rehearsal.

The trumpet part would be much better written like this:

This way, it matches the bass part in phrasing and articulations. No questions.

One thing to mention is that the way articulations are notated can change from instrument to instrument. You can change the articulation to reflect the instrument’s technique, while getting the same sounding result.

Here, for example, the bass part looks strange with a big slur over it. The bassist will either pluck each note individually or play a few at a time under one slur (as a hammer-on), as shown in the corrected example.

This is even more important when dealing with ensembles that have classically-trained and jazz-trained musicians. You should articulate and notate all horns the same way as each other, but a classical violinist and a jazz trumpeter seeing a marcato will not interpret it the same. It’s not uncommon to have parts that look to be articulated very differently but will get the same result, depending on the player, their instrument and their background.

Some arrangers come from the school of thought that you should put the same articulation on every instrument to show your intention and let the players work out how to achieve it. For the example above, both the trumpet and bass would get long slurs to show a smooth line, although it doesn’t reflect how you’d execute it on a bass. I use this sometimes too, but it saves a lot of studio time to notate it exactly as you want the phrase to be played for each instrument.

Un-matching The Phrasing

Sometimes, the backing track is wrong and the parts are correct. Everyone is on a time crunch and backing tracks are often prepared hastily. In that case, I’ll make a note to ‘ignore track phrasing’ or to ignore a specific instrument. If the track is really in the way, I’ll just record to click. Again, this can avoid so many questions. When the players hear the backing track and see that their parts don’t match, it takes a lot of time to sort out which could have been avoided by careful arranging or simple instructions in the parts.

PHRASING EXAMPLES

The main things you should be looking for when checking phrasing are the following:

Note length. Do my note lengths match the track and the other players around me when they’re supposed to?

Articulations. Are my lines phrased the same way?

Rhythms. Do rhythms contradict each other or not work together?

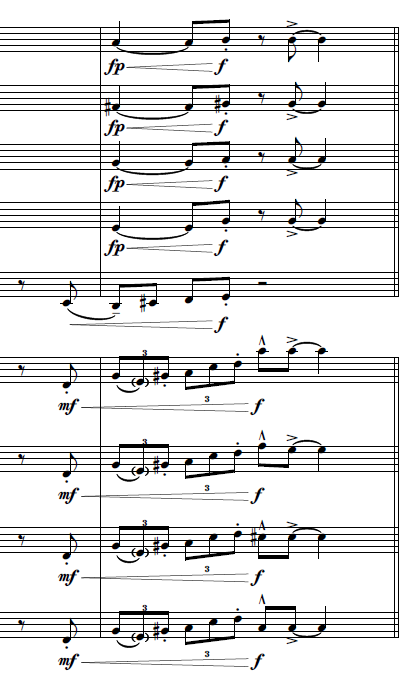

Here are a few more examples of bad phrasing that could raise questions. The players might fix them themselves or they could cause problems with phrasing if they played as written.

First, this example, where the trombone finishes before everybody else:

Secondly, these rhythms mean the staccato dots don’t fall in the same place - the triplet rhythm in the trumpets clumsily crosses over the 8th note sax rhythm. If this is intentional, I’d make a note of it in the parts (‘play against trumpets’ or something) so there wouldn’t be a question, but it would be probably more effective if they all played this together anyway:

Thirdly, in this example, the trombones have an extra note leading into the double bar line compared to the trumpets and saxes. This isn’t the end of world but the saxes and trumpets are going to breathe before their ff entry, whereas the trombones won’t. Pros will ask what you (the arranger) what to do about it. Another wasted couple of minutes!

BEAMING

Finally, I should briefly mention something about writing rhythms. We come across a lot of syncopation in big band writing and every effort should be made to make the notation as clear as possible. It’s often useful to beam over rests (but don’t use stemlets!) to show the beats clearly.

Take the following example which is confusing to read:

This is much better when written like this, where each beat is shown by the beams, the triplet is replaced with a turn, and the last rest omitted with an articulation that will get the same result. The beats are clearly shown and the phrase is easier to feel and read. When in doubt with any syncopation, make sure the beaming shows the beats as clearly as possible.