18 | The Rhythm Section (Part 2)

This is part 2 of my article on The Rhythm Section. Check out Part 1 here if you haven’t already. In it, I cover general rhythm section notation conventions and specific writing for guitar and piano.

BASS

This is of particular interest to me as a bassist so I might go on for a while. The choice of whether to use a double bass (also called acoustic, upright or my favourite, the bull fiddle) or an electric bass is determined by the style and/or the arranger. Swing, jazz and ballads will by default be played on a double bass. Rock, funk and latin will be on electric. The bow is rarely used on a double bass and pizz. is assumed without being written - in fact, writing pizz. at all leads to confusion (‘should I have been arco at some point?’).

The strings are tuned to E A D G with an extra low B on a 5-string electric. It can be assumed that a pro will have at least one 5-string electric that they could bring if they don’t play on one normally. It’s good to check ahead of a recording session but for other contexts, the bassist will just put any out of range notes up the octave.

The double bass in a big band will be usually set up for jazz and won’t have a C extension or 5th string. However, if the bassist is a theatre pit player or frequently does classical or crossover gigs, they might. Regardless, I would avoid writing for double bass below the low E.

The bass generally is the link between the drums and piano, playing the foundation of the harmony and providing the rhythmic pulse. A bass player can sometimes be called upon to take a solo if the texture is sparse enough.

For both basses, two fingers on the right hand are used. On electric bass, all four fingers on the left hand are used to stop notes, whereas on double bass, due to the positioning system, only three fingers are used. Figures that are easy on electric aren’t necessarily easy on upright.

The electric bass is more agile than the double bass in general and has a more focused sound. All professional jazz bassists should play both, but they’ll still have a preference for one or the other. Most jazz players begin on electric and move to upright so for amateur players note that intonation and technique may be stronger on electric bass.

Notation

The bass player unsurprisingly reads bass clef and both the double and electric bass sounds one octave lower than written. Like the guitar, don’t use a bass clef with an 8vb symbol, it just causes confusion.

8va is fine for electric bass but should be avoided for double bass. Tenor clef is standard for double bass in the classical repertoire, as is treble in the solo rep, but jazz players generally stick to bass clef. If you really need to go high on an upright, treble clef is preferable and you’ll need to give most pro players a few minutes to work it out (does it really sound that great up there anyway?).

Here are the most common types of notation for bass:

Chords With Slash Notation

Written Out Lines

Grooves & Riffs

Chords With Slash Notation

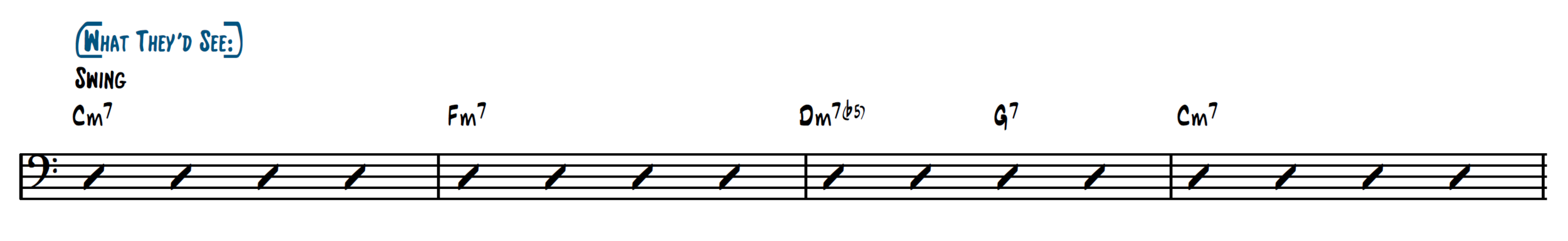

Like guitar and piano, if a bass player sees chords and slashes they’ll accompany in a stylistically appropriate way. This varies quite a bit from genre to genre with bass. In a swing chart the bass player will ‘walk’. Walking is when the bassist plays a melodic bassline linking the chords together, often with chord tones on strong beats and passing notes on weak beats. If the style is swing and the player sees chords and slashes, no bass player is going to do anything other than walk, so you don’t need to write ‘walk’.

Under no circumstances should you write out a walking line unless:

You’re a bassist and you know what you’re doing. (Even then, probably don’t).

It’s doubled in another instrument like left hand piano, bari sax, bass trombone etc. Then it’s fine to make sure everyone is playing the same part.

It’s really frustrating to be baby-sat with someone else’s walking line. Often when the chords are familiar like rhythm changes or a series of ii-V-Is, the bassist can go onto autopilot and focus on upcoming areas of the music or listen to the performance and really think about how best to lift and support it. If the walking line is written out, it’s often janky and not that idiomatic and takes all the player’s concentration to navigate it. Good walking lines are melodic, artful lines in their own right, not just harmonic filler under the band. Rant over.

Walking lines can have a note on every beat or two notes in a bar. This is known as playing ‘in 4’ and ‘in 2’ respectively. The tempo text would usually have ‘in 2’ so the drummer would know too, or a time signature of 2/2 or cut common.

Without specifying in 4/4, the default is walking in 4 but you can write ‘in 2’ under the slashes and you’d get a half-time feel of two notes per bar. Half notes are often used to hold back and then playing in 4 gives the chart drive. It’s also common for the bassist to switch between playing in 2 and in 4 every few bars early on a chart to give the lines shape.

In other genres, slashes could involve the bassist coming up with a riff, groove or pattern that they use while supporting the chords or playing simple root notes and important chord tones to hold down the harmony. Certain genres will give the bass player a framework to work within (a latin chart with a 2-3 clavé will mean the bassist will play a specific tumbao pattern for example) so usually a stylistic indication and the chords and slashes are enough.

Here are roughly the same chords as the swing example above but with different stylistic indications. Notice how the playing changes dramatically with each genre/style (and so does the use of electric/double bass):

2. Written Out Lines

After that rant on walking lines, there are some occasions where it’s fine to give the bassist some direction. If they need to play in a specific register or match certain other instruments in the band, it’s fine to write out lines for the player. It’s also fine to mix and match slashes with standard notation.

Here, the player will play the first two bars in half-time (in 2) with two notes to a bar. Then, I’ve specified the exact notes to play in the last two bars, maybe because the piano or horns are doing the same thing that the bass needs to match:

This gives the player freedom while also ensuring they stay in a register you want. This is especially useful when you need the bassist to hit a particular octave if the bari sax or bass trombone is quite low. When quavers are used for momentum, the second note is usually an open string D or A while the player shifts position. Bassists will thank you for these or put them in themselves.

Notice that rhythmic notation isn’t listed as one of the notation options. It’s not uncommon to see in bass parts and it is used sometimes with chords over the top, but as the bass will be playing single notes anyway, it’s usually just better to write the rhythm you want with the notes you want i.e. just use standard notation:

3. Grooves & Riffs

Grooves and riffs form a big part of rock and funk bass-playing. These can be written out for a few bars and then the player can be left to improvise based on the pattern around the chords. As I mentioned previously about repeat markings, I’d rather see a complex pattern written out over and over than bar-repeat markings. Being a bassist, I often like to write out a suggested groove and write ‘ad lib’ over repeat markings. When the chord changes, the bassist will continue in a stylistically appropriate way.

This isn’t quite the same as using slash notation as the player will still follow the guide groove you’ve given to some extent, mainly rhythmically. With slash notation they improvise completely. I don’t mind bar-repeat markers in this situation as I don’t really have to look back at the initial few bars for the groove over and over again - if it didn’t say ad lib then I’d just repeat the groove over and over rather than use these bar-repeat symbols.

Articulation

Like the guitar, all articulations are possible on the bass that are available to horns. The same advice with regards to slurs applies here as it did to the guitar. Palm-muting is also available on electric bass but is much less common than guitar.

In rock charts, a bassist may choose to play with a plectrum or pick. It’s a tone choice and the arranger can specify or the player can decide. Either way, it won’t break a chart if you do or don’t specify. You can write ‘with pick’ and then ‘fingerstyle’ to go back to normal.

Dead-notes are little ‘x’ noteheads and are just percussive hits with the right or left hand - you’ve probably seen me use them a lot in these examples to notate exactly what the bass is doing. They can be effective in funk and rock charts, as well as notes that are felt rather than heard in walking lines. They’re also really useful in between big leaps on the bass, as are open strings, to cover up position shifts. I wouldn’t worry too much about writing these in apart from maybe specific funk lines: they’re put in instinctively by the player.

Slap Bass

On electric bass, the one most commonly misused technique by arrangers is slap. Slap bass involves using the thumb (T) to hit and index finger to pop (P) strings, creating a percussive, funky sound. It’s annoying to be given a micromanaging bassline like this:

I actually see lines written like this, probably because the arranger has looked for notated slap lines and come across educational material where this kind of specific annotation is useful. In the context of a chart though it’s a mess.

It would be a bit more acceptable if it’s a big bass feature or a really specific groove. You’d also have to make sure it was very accurate as slap patterns work best in certain groupings and contexts (for example, loads of fast pops after each other doesn’t work). Each bassist is different and has a slightly different technique for slap (thumb up or thumb down etc.) and arrangers always underestimate how much thumb is actually used in these grooves. The percussive nature of slap means there’s a lot of dead notes involved too which are often player-specific based on patterns they have internalised. It’s rare to write a line like this so specifically and it also be comfortable and idiomatic. It also just looks kind of messy to write this out so specifically.

It’s best to just write out the groove and the word ‘slap’ over the top - let the player figure out the pattern and then use ‘fingerstyle’ to go back to the usual way of playing:

This way, you also get some personality of the player into the groove as there are a lot of different ways a slap line can be played. Players can go from fingerstyle to slap and back very quickly but it’s best to give some time to prepare.

Here this groove uses dead notes and is probably the most I’d use without micro-managing the bass player. Patterns of continuous 16th notes are often very idomatic to slap as it’s easier to keep the pattern and hand moving once it’s started:

There are also a bunch of other off-shoot extended techniques like double-thumbing and that the arranger doesn’t need to worry about notating, but the player may use depending on the groove or style.

Tuning

Like the guitar, the electric bass doesn’t always stay in standard tuning. It’s assumed in a big band that the electric bass will be in standard, but the other option, although rare, is Drop D (D A D G). This drops the E string on a four-string bass down to D giving an extra tone of range. This is more idiomatic of rock charts. Some bassists have a ‘hipshot’ tuner which is a little lever attached to the back of the headstock allowing for near-instant E to D tuning changes and back.

Of course, most players will have a 5-string available so you should feel free to write down to the low B. If a 4-string player doesn’t have it, they’ll just put it up the octave.

Effects

Like the guitar, although not as many, the electric bass has a variety of effects available. The most common are filters (for funk), slight overdrive (for rock) and octave pedals, raising, lowering or adding octaves above or below to the fundamental note being played. These should be specified above the stave and shouldn’t be taken for granted in a big band without asking the player.

The double bass has no effects traditionally available but is often amplified nowadays with pickups that attach to the bridge. No notation is needed for a double bassist to amplify and the player will decide this based on context.

Bass Part Layout

Here’s an example of one of my bass charts. Notice it just says ‘Bass’ but due to the swing indication, it will be played on double bass by default:

DRUMS

The drums in a big band are more than just a time-keeping device. They provide the energy and encompass the emotional arc of the whole chart with solid, strong (not necessarily loud) playing while serving the arrangement. A good drummer will play hits with the band, play fills to enhance the arrangement and support the structure of the chart.

A great drummer will set up these hits with the band (called cueing), helping the players find their entry together and then play the hit with them. This combination of cueing and then hitting the accent is sometimes called ‘kicking the band’. These hits are therefore sometimes aggressively called ‘kicks’ more generally or ‘punches’ for a specific rim-shot snare accent. This process is also more rarely referred to as ‘making cuts’ with the band.

It should be clear now that the drummer is a player who takes on a lot of responsibility. A great drummer can really elevate a big band’s sound as a whole. The best drummers will think incredibly musically, not only rhythmically. They’re also listening to the harmony and ensemble, helping cue and colour the band where needed.

Notation

The drum kit is written on a five-live stave with a percussion clef. Drum notation isn’t completely standard unfortunately and what’s worse, it seems to slightly differ specifically from US to UK usage.

The most confusion comes from where to place the hi-hats and ride. In the UK, I see the hats put above the stave most often (where the ‘G’ would be in treble clef). In charts from the US, they seem to be put in the top space of the stave. The solution I use is a mixture of the two to avoid all potential conflict:

The hi-hat goes in the top space. The ride would never go here in any system so every drummer would know this is a hi-hat.

The ride goes on the top line. This means I don’t use the space above the stave at all, avoiding all confusion with whether it’s a hi-hat or ride.

In general, anything played by the feet (the bass drum and hi-hat foot) has a stem going down, anything played by the hands has stems going up. It’s annoying for drummers to see things other than this, especially for complex grooves. You shouldn’t delete rests between kick drum parts either, even if you think you’re making it look cleaner.

I would stick to this rule apart from where the groove has a kick and snare part that work so closely together and would look messy with stems going up for the snare. That would be very rare though. Here are a few examples:

There are three ways that a drum part can be notated in a big band chart:

Slashes (And Kicks)

Rhythm Notation

Written-out grooves/fills

Slashes (And Kicks)

The most common form of drum notation is slash notation. Without specifying anything, the drummer will play ‘time’. You can write this too, but it’s pretty redundant. Playing ‘time’ means that the drummer will accompany the band and groove along in a stylistically appropriate way. In an up-tempo bebop chart, this would be by playing a swing pattern for instance.

These slashes obviously don’t need chords but often have figures that the band (usually the horns) play in small noteheads above the stave. This helps the drummer navigate the chart and also set-up important cues and kicks. Below the stave, more small noteheads can be added for more kicks, usually those of the bass instruments:

You shouldn’t be selective with what cues to give the drummer - the full picture is always better so they can make informed decisions about their cueing and kicks. In a fast or unusual chart, it could be dangerous to omit notes of a cue too as the chart won’t match up with what the drummer hears.

Once a pattern has been established, repeat symbols can be used. Be sure to use small numbers in brackets to show how many bars have passed doing the repeated figure. Take this simple swing ride groove for instance:

I usually use slash notation for general ‘time’ and repeat markers for specific repeated patterns like this one. The main thing is keeping it consistent.

2. Rhythm Notation

Rhythm notation stops the groove or time and instructs the drummer to play a specific rhythm. Stopping the time or groove so should be used only in moments of impact - often slashes with kicks showing the rhythmic stabs is better than having the drummer stop everything to play just the rhythmic hits. Here’s what they’d see in the part and how it might be played.

3. Written-out Groove/Fills

Writing out exact grooves is a dangerous business unless you know what you’re doing. One thing that is useful though is giving a groove as a kind of ‘template’ for the drummer to work off. It could show where the snare is to be placed or the kind of hi-hat rhythm to be used for example, while still giving the drummer the freedom to improvise around that groove.

Never write out a full drum part in every single bar using only notation. That’s incredibly micro-managing and slash notation will get a much better result. Most of the time, you won’t get close to the complexity a drummer is actually putting into the groove with ghost notes on snare drum and feathering the kick drum, so it’s best just to give a general groove and let the player ad lib.

If a specific pattern or groove is necessary, writing it out for a couple of bars and then using repeat symbols is fine:

Writing out fills isn’t unheard of and can be a good way to show what kind of fill you envisage. More often than not though, I leave the slashes in and indicate fill over the top of the stave with a line.

Sticks & Brushes

In jazz it’s not uncommon for a drummer to play with brushes - retractable metal prongs that are played on the cymbals and in circular motions on the snare. They’re a soft sound usually reserved for ballads. Sticks will always be default unless you specify brushes. Drummers can change quickly but it’s best to give some rest for them to switch. If really necessary, they can play a lot of grooves with one hand while they turn pages or change from sticks to brushes. To indicate brushes, just write ‘brushes’ above the part and then ‘sticks’ when the change is needed.

Over-Notating, Articulations & Only Having Two Hands

The general rule of thumb with drums (and all rhythm section parts) is to avoid over-notating. They don’t need every intricacy of a MIDI groove written out to play well. Usually, they just need to know if they should be playing time (with slashes), a groove, and/or kicks with the band. Adding anything more than that should be considered carefully.

As for articulations on cues and rhythm notation, things like slurs are redundant. I like to include all of the tenutos, accents, staccatos and marcatos on the kicks to give the drummer the full picture. Just because they’re percussion instruments doesn’t mean they can’t get a wide variety of note length and colour.

When a crash or ride cymbal needs to be stopped immediately you can write ‘(choke)’ in brackets above. If you use a marcato or staccato, the drummer will also probably choke it. A drummer can do this with one hand but usually needs two so avoid writing a snare or any other hit during this.

Sometimes, instead of a ‘choke’ marking or an articulation, I see tramlines in parts for this. I really don’t like this as it’s a common symbol for stopping in theatre pads and it could be misinterpreted as a symbol to stop playing.

On that note, a drummer only has two hands. Refrain from writing for three drums that need the hands at once, especially on impactful hits.

Drum Part Layout

Finally, as I’ve done for each rhythm section instrument so far, here you can see an example of one my drum parts: