9 | Jazz Harmony

Having a working knowledge of jazz harmony is vital to the big band arranger. My question is how little can you get away with and still sound convincing? Like I said in my intro post, as these articles are for arrangers and composers with some experience already, I’m not going to dive into basic details and assume a good pre-existing music theory knowledge.

This is quite long and dense - I’d probably get a coffee. It should hopefully be a quick-ish primer before moving on to the actual arranging stuff.

CHORD EXTENSIONS

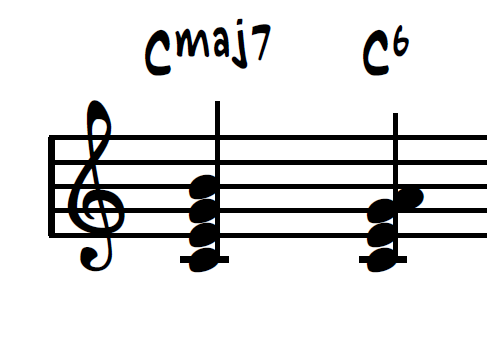

Chords in jazz are most often extended past simple triads. By default they are usually either made into a 7th or a 6th chord:

We can also go further than the 6th or 7th, and add 9ths, 11ths and 13ths. Depending on the basic 7th or 6th chord, different 9ths, 11ths and 13ths may be added and/or flattened or sharpened based on the context.

These extensions (the 9th, 11th, 13th and their alterations, b9, #11 etc.) are referred to as available tensions. If a performer sees a simple Cm7 chord, they may choose to embellish it with extra tensions like the 9th or 11th.

Tensions can be harmonic or melodic. That is, they can either be part of a chord, or be played in a melody. It gets a bit complicated as some tensions are allowed to appear harmonically, but not melodically in certain chords, and vice versa. I’ll talk more about that later.

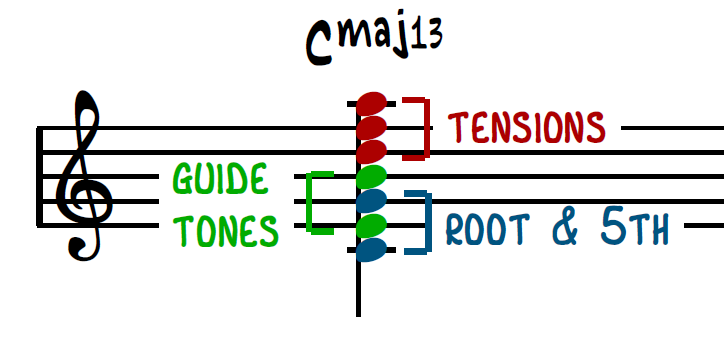

It’s important to note here that if a chord symbol says Cmaj13 for instance, it also includes all extensions up to the 13th; the 7th, 9th and 13th would be played too.

Guide Tones

Guide tones are the lifeblood of jazz. The guide tones of a chord are the 3rd and 7th. They tell us the quality of the chord and good voice leading relies on these voices moving smoothly between each other.

All of the notes in a chord have specific functions. Here are some labels we give to certain notes:

Avoid Notes

So why do I specify available tensions? That implies that some are unavailable to us. Avoid notes are tensions that would create too much unpleasant tension if we added them to the chord. This is usually due to them creating a minor 9th interval somewhere. To get around these unavailable tensions, or avoid notes, we either, well… avoid them, or we substitute them for more pleasing, available tensions.

There are two very common avoid notes that come up all the time. These shouldn’t be used harmonically, but melodically in passing is usually just about alright.

One is the 11th in a major 7 chord. The 11th has such a strong pull to our important guide tone - the 3rd - that we usually make any 11th on a major 7 chord a #11 instead.

The other is the 13th in a minor 7th chord. We have nearly the same problem here: the 13th is only a half step away from our important guide tone - the 7th. As the 13th is also the 6th, it kind of confuses the fundamental chord quality - is it a minor seven or minor six chord? We usually just avoid this one altogether if the music is not modal.

All Available Tensions

You have probably gathered now that it’s not quite a case of ‘play any note with any note and it’s jazz - it will work!’. Fortunately though there are simple intervallic rules that tell us what our available tensions are. This table applies to the chord tones we can use harmonically. You have a bit more freedom melodically, but care should still be taken with unavailable tensions on strong beats.

I’ve compiled a table of common basic jazz chords and the available and unavailable tensions below. It’s quite safe, but if you stick to writing chord symbols like that for now with these chord tones, nothing will look or sound out of place.

For instance, if we had a C minor 7 chord, the table shows that we could also add the 9th (D) and the 11th (F), but not the b5, b9, #9, #11, 13 or b13.

Using the table, a good rule of thumb to memorise is:

Major chords can have the 9th or #11th added.

Minor chords can have the 9th or 11th added.

Dominant chords can have anything added.

MAJOR 7 CHORDS

There is one very important reason why we substitute notes for available tensions other than for colour. Let’s a Cmaj7 chord with the root on top. This creates dissonance between our melody note (C) and our major 7th (B). No matter where we put our B, if it’s below the C we get either a minor 2nd interval, or worse a minor 9th. This is very dissonant. To solve this, we have one of three options:

Make the major 7 chord into a major 6 chord instead.

Substitute the root of the major 7 chord for the 9th.

Keep the root of the major 7 chord below the 7th at all times.

This is why we often see C6 rather than Cmaj7. Something to be wary of as we continue.

OTHER COMMON JAZZ CHORDS

There are a few other chords that crop up from time to time that are good to be aware of, as well as what their available tensions are.

6/9:

A 6/9 chord is a major 6 chord with a 9th too. You can also add a #11 as another available tension. Minor 6/9 chords are also found which is the same construction as below but with a b3.

A major 6/9 chord is: 1 3 5 6 9. A minor 6/9 chord is: 1 b3 5 6 9.

Minor/major 7:

The available tensions are the same as a regular minor 7 chord - the 9th and 11th can be added freely. Like our major 7 chords, the B, if placed below the root could easily cause unwanted minor 9th intervals. Be sure to keep it above the root in min/maj7 chords.

A minor/major 7 chord is: 1 b3 5 7.

Minor 7b5:

Familiar to those in classical music theory as a half-diminished chord. You can add the 9th (if the min7b5 chord is diatonic to the key of the moment), and the 11th and b13th.

A minor7b5’s formula is : 1 b3 b5 b7.

Augmented 7:

A dominant 7 with a #5, this chord is used fairly frequently. You can add all other tensions to an augmented 7. Sometimes maj7#5 chords are found but are rare.

An augmented 7 is: 1 3 #5 7.

7sus:

A suspended 7th chord is a dominant 7 chord with a suspended 4th. All other tensions that don’t interfere with the 4th (or accidentally add a 3rd, like a #9) are valid.

A 7sus is: 1 4 5 7.

Altered Chords

Altered chords in jazz aren’t quite the same as an altered chord in traditional music theory. They refer to dominant 7 chords that have one or more of these tensions added:

#5, b5

#9, b9

b13

Any dominant chord with one or more of these tensions can be correctly said to be altered. Often, the chord symbol will just say ‘alt’ (e.g. C7alt) and the performer will decide the exact tensions to use. Here are some voicings that a performer could potentially play if you just wrote ‘C7alt’:

Take care not to use conflicting altered notes. Writing C7(#5, b13) would make no sense. #5 and b13 are the same, as are #11 and b5. Note that the #9 is enharmonically the same as a minor 3rd, so 7#9 chords effectively have both a major and minor 3rd, although the minor 3rd is functioning as a #9.

Using altered notes along with their natural ones isn’t advisable. So a 9th with a #9, or 5th with a b5th for instance wouldn’t really work. #9 and b9 together would be fine though, as would #5 and b5.

Note: Altered chords are bit more nuanced than this, and using the word ‘altered’ implies using a specfic mode to improvise with. For our purposes, using the chord symbol ‘alt’ is a bit of a catch-all but will do for all our purposes. See the further reading at the bottom of this article if you want to get into the specifics.

Polychords & Slash Chords

Adding a lot of tensions to chords make them difficult to read quickly, especially for pianists. We can break down otherwise complex chords into easily-readable chunks. Imagine a chord with the notes C E G B D F# A. Sure, it’s a Cmaj13#11 but could also be written like this:

This would mean playing a D major triad (D F# A), over Cmaj7 (C E G B), creating a total chord of Cmaj13(#11).

Polychords aren’t be confused with slash chords:

Slash chords show the inversion by specifying the bass note which may or may not be part of the chord already. Note that pianists and guitarists often play rootless voicings. These don’t need slash symbols - only when the arranger wants the bass or lowest voice to play a specific bass note other than the root are slash chords required.

Polychords are written with a horizontal line, and slash chords with a diagonal line. They can sometimes be ambiguous to read, so check if the lower letter has a chord symbol, or what would make most sense in context, checking against the bassline. Slash chords are generally more common than polychords.

CHORD SYMBOLS

There are a variety of notations available for chord symbols and they are not all equal. Some are distinctly better than others. Here’s a table with the possibilities for each chord type and my recommendations on which to use.

The ones in green offer what I think is the least ambiguous option, while also saving time and space.

The orange ones show symbols that are encountered frequently but are either quite long to write out or could raise questions. (For instance, some charts use △ without a ‘7’ for a major triad, some use it for a major 7, so it’s better to avoid confusion and use maj7 or △7.)

The red options should not be used in any circumstances because they cause more problems than they solve. M7 can be confused with m7. m/M7 has the same issue. 7#5 isn’t ideal because we read left to right. By the time the player has played a dominant 7 chord, they might miss that the 5th has to be a #5. +7 is far better because it ensures that mistake won’t be made.

Looking in the most recent Real Books will show a mixed use of maj7 for major 7 chords and -7 for minor 7 chords which offers the clearest, most question-free, approach.

Brackets

For chords with many added tensions, like altered chords, we usually use brackets to keep the chord symbol looking clean and tidy. Without the brackets, it’s like using a sentence without punctuation. Without trying to resurface any maths class PTSD with bracketed formulas, compare the following. These chords could mean quite different things.

The first could be seen a D chord with a b13, or a Db13. Ambiguous. The second example is definitely a Db13. It would be better to write the first chord as D7(b13). The ‘7’ helps separate the letter from the accidental.

There’s no hard and fast rule, but writing the tensions in the order they’re to be played keeps it clear, and using all possible vertical space is good too. Just consider whether or not it might just be worth writing ‘alt’ if you’d get the same effect.

Naming Complex Chords

Generally, you should aim to name chords in the shortest, most concise way possible. The chord above - Db13(b9,#11) could probably be written Db7alt with no noticeable affect on the sound. I often leave all chords as simple 7ths and let the players add their own extensions.

The one thing to be aware of is when to use #5 versus b13 and #9 versus b3.

C7b13 will have a natural 5 (G) in the chord and an Ab, whereas C+7 will not have the G.

In a chord with a major and minor 3rd, the major 3rd always takes priority in the chord symbol. The chord is a major or dominant chord. The b3 functions as a #9 instead.

For example:

Let’s take the random collection of pitches: Fb G Db C Eb Bb Ab.

If we respell Fb as E then we have C E G Bb - a C7 chord. The Db is a b9 and the Eb is really a D# (#9) because we already have the major 3rd that takes priority. The Ab is definitely a b13 because we have a natural 5 (G) and a 7th (Bb) so it can’t be a #5 or a b6.

Still with me? This chord is therefore best spelled as a C7(b9,#9, b13) or, better yet as just C7alt.

THE ii-V-I

The backbone of jazz is the ii-V-I chord progression. Most chord progressions, if they’re functional, can be seen as big elaborations of ii-V-I progressions, just with alterations, reharmonisations and substitutions.

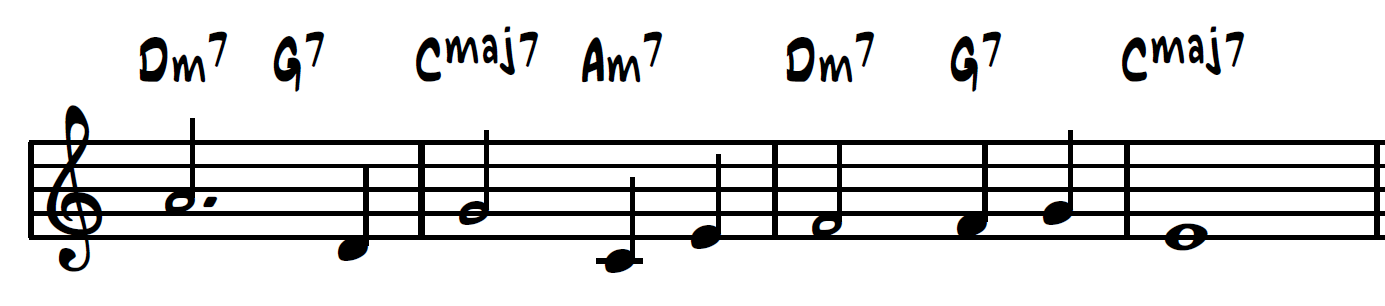

The major ii-V-I looks as follows:

Note the smooth voice leading of the guide tones in pink. The 3rds and 7ths swap with each chord which is characteristic of ii-V-I progressions (i.e. the 7th of the Dm7 chord becomes the 3rd of the G7 chord which then becomes the 7th of the Cmaj7 chord).

Cmaj7 could easily have been substituted for C6.

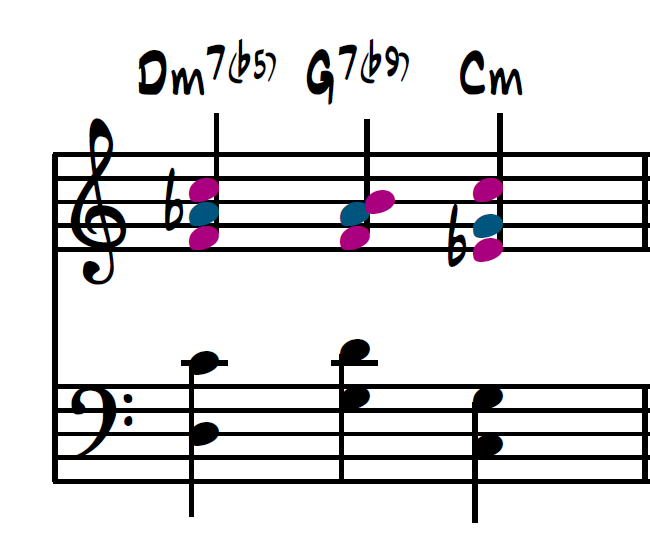

In a minor ii-V-i, a V7 chord leading to a minor i chord will often be made into V7(b9). For instance:

Notice the additional voice in blue: the added Ab in the G7 chord is carried over from the Dm7b5 chord and resolves to the 5th (G) in the Cm chord effectively.

Chord Function

Like other tonal music, each chord in a ii-V-I has a function. The function is the tendency of each chord, to hold tension or resolve, determined by the interval movement between chords. These functions, like in classical music, can be broken down into subdominant, dominant and tonic function chords. The function of the V and I chord are obvious. These dominant and tonic functioning chords create tension and then release.

The ii chord however is interesting in a jazz context. In a major key, the ii chord is a minor 7.

This means that in functional jazz, when we see a minor 7 chord, it behaves like a ii chord.

That’s really important. (There are some exceptions to that like if the minor7 is a vi chord, or the music is not functional i.e. modal, which we’ll get to later).

When we want a minor chord that acts like a tonic chord, we therefore don’t usually use a minor 7 chord.

It’s a common mistake to make. Instead, we use just a minor triad or a minor 6 chord instead for a tonic functioning chord.

Secondary Dominants

Secondary dominants are used all the time in jazz, especially leading to the ii chord. A common chord progression other than the ii-V-I is I-vi-ii-V. The vi and ii chord can be made into dominant 7 chords and become secondary dominant chords. VI7 is the secondary dominant of II7 which is the secondary dominant of V7.

These are known as rhythm changes and come from Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm. They’re really common in jazz charts and are usually played in Bb.

In the original tune, the progression is Bb, Gm7, Cm7, F7, but the term ‘rhythm changes’ has also come to mean reharmonising the first chord with I6 or Imaj7 and the vi and/or ii chords with their secondary dominants.

Linking Chord Progressions Together

It’s very common in jazz (and most tonal music come to think of it) for chord progressions to link into other ones. For example, the I chord of a ii-V-I progression often is made into a minor 7 and becomes the ii chord of another ii-V-I progression and so on.

In the following example on non-chord tones, you’ll see a progression that starts as a ii-V-I in C and the Cmaj7 becomes the start of rhythm changes. At the end of the rhythm changes, the Cmaj7 is made into C7 for a modulation into F. It is this kind of constant overlapping of progressions that gives jazz it’s momentum.

NON-CHORD TONES

We know that chord tones are really important in jazz. What about the other notes in between, though? They’re just melodic tensions really most of the time. We have these in classical music theory too and we call them suspensions, retardations, neighbour notes, appoggiaturas etc. We still get these types of non-chord tone in jazz, but the main type is known as an approach note.

In jazz any note just below or above a chord tone is an approach note.

Approach notes help us colour the lines so we’re not just playing chord tones all of the time. They can be a tone or semitone away from our target note and usually fall, but not always, on weak beats. They’re either chromatic or diatonic and depending on which they are will influence how we harmonise them later. For now, check out the example below showing a line with and without approach notes.

The first approach note is an F# - an accented chromatic approach note that happens to be a blues note of the chord at the time (#4 of Cmaj).

The second note, D, is a passing tone between two chord tones of C and E.

The third approach note is a neighbour note between two chord tones. The first F is the 3rd of the Dm7 chord and the second F is the 7th of G7.

Enclosures

Enclosures are what we’d more traditionally look at as double neighbour notes. They involve two approach notes, one below and one above the target note. Again, they’re usually found on weak beats, but not always.

Rhythmic Displacement

The nature of jazz means that the melody often becomes syncopated. It’s important to understand where the harmony changes occur and how they relate to the melody. Usually, the target note is moved just ahead (anticipated) or just behind the chord change, but still belongs to that chord. This affects how we’ll harmonise these target notes later.

SUBSTITUTION & REHARMONISATION

Substitution is common in jazz, done either by arrangers looking to swap out chords for different flavours, or done by players on the spot. Usually, in functional harmony, we swap out chords that have a similar function so the tension and release of the music is kept.

The most common kind of chord substitution is tritone substitution. This involves taking the V chord and substituting it for a V chord a tritone away. In this case, G7 is substituted for Db7:

This works because the guide tones in G7 (B and F) are the same as in Db7 (F and Cb), so the tension needed to resolve to Cmaj7 is still there. The Db7 chord also creates smooth voice-leading from Dm7 to Cmaj7 in the lowest voice.

Other substitutions include things like swapping maj7 chords for vi-7 (i.e. Cmaj7 to Am7) and other functionally comparable examples like ii-7 and IVmaj7 (Dm7 to Fmaj7). There are a lot of different substitution options but as long as it’s just the flavour you’re changing and not the function, most will work out just fine to get started with.

Reharmonisation

Reharmonisation is kind of like substitution on steroids. It involves reworking whole chord progressions and can include adding, extending and completely removing chords. A common way of reharmonising is to add ii-V progressions before certain structural chords, effectively ‘tonicising’ them. There are a lot of other ways that are beyond the scope of this article, but I’ll link some good resources for further reading below.

To reharmonise, you can look at the melody and come up with a convincing chord progression and bassline that voice-leads well. Reharmonisation is a personal and creative thing so I can only really offer two pieces of advice to follow:

Make sure the reharmonization is structurally sound. Progressions shouldn’t resolve too early, or have a lop-sided harmonic rhythm (4 chords in one bar and then 3 in the next can sound weird).

If the music is functional, make sure you reharmonise in a way that supports this. V will always want to go to I and ii-V-Is are your friend.

Sometimes, you can just use chords because they sound good without any good reason.

Here’s an example reharmonisation from a well-known Real Book tune:

Notice the harmonic rhythm is now faster but still consistent. It doesn’t slow down until the final cadence. I’ve kept it simple, only adding ii-V-I progressions, rhythm changes and the occasional substitution or secondary dominant.

CHORD-SCALE THEORY

Chord-scale theory refers to a theory used by Berklee Press and by Mark Levine in both The Jazz Theory Book and The Jazz Piano Book.

The general principle is that, in functional music, a chord symbol implies a specific scale to be used over it.

I have many issues with this way of thinking for teaching jazz. One of my issues is that it encourages composing melodies and soloing using scales. Scales are not used for soloing or creating melodies - chord tones, tensions and approach notes are. Blasting up and down a D minor scale does not an interesting solo make.

However, used as a harmonic tool, rather than a melodic one, I think chord-scales have their place. Scales are just collections of pitches. In that sense, they are useful to us as arrangers. They give us the available notes we can use to harmonise any given target note.

Chord-Scales 1

Let’s take this melody:

We now want to harmonise each note in our melody. In a diatonic setting we’d usually think of C7 as the V chord in F major. So to figure out what notes we can use, we have to write out an F major scale, starting on C:

This gives us all our available pitches which we can use to harmonise the melody. I’ve made each note into a C7 chord by hanging notes underneath the melody:

This ensures our harmonies are consistent with the function of the chord; everything stays neatly in F major. All of our harmonies support this C7 as a V chord in the key of F. This is a pretty obvious way to harmonise, regardless of genre. But we can go further.

Chord-Scales 2

If we had the same melody, but a different chord, we’d use a different chord-scale, so we’d get a different harmonisation:

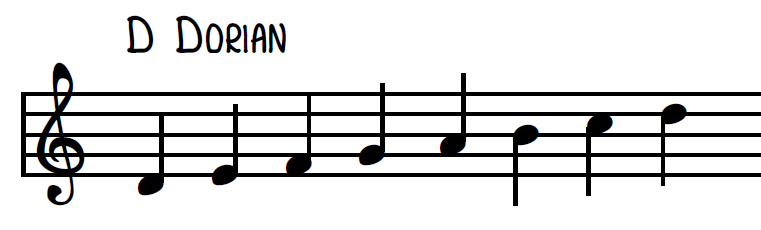

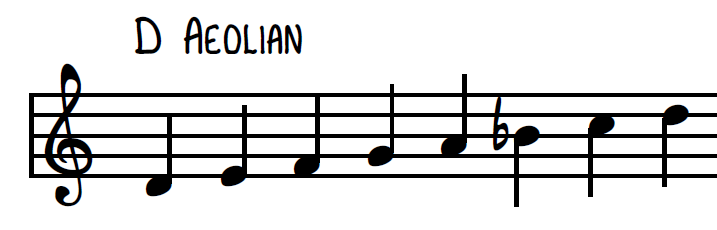

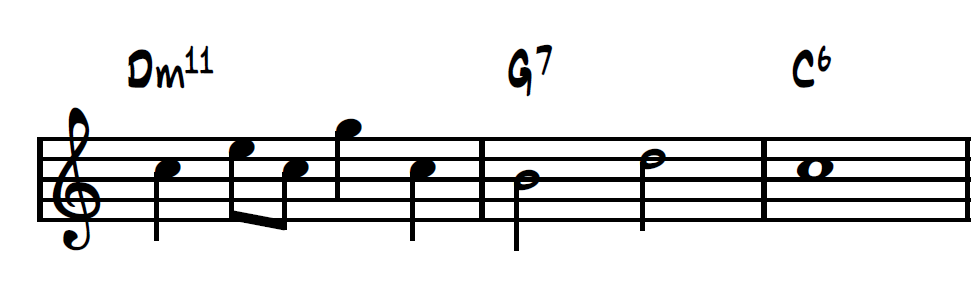

Dm11 could be a ii chord in C major or a vi chord in F major. We don’t have enough information to know the context, but it is important that we get it right. Depending on the function, the chord-scale for the Dm chord will change.

We’d use D Dorian for a ii chord in C major, and D Aeolian for a vi chord in F major. We need to know the function of the Dm11 chord otherwise we could use either a B natural or Bb incorrectly. Harmonising the chord incorrectly would take us out of the key of the moment and stop our chords from functioning properly (V wouldn’t lead nicely to I, ii wouldn’t lead nicely to V etc.)

After the Dm11, the chord progression could continue in a number of ways. Here are just two possibilities:

In the first example, we have a ii-V-I in the key of C major and the Dm11 is functioning as the ii chord. Therefore, we can harmonise the melody with the correct chord-scale (D Dorian).

In the second example, we have a vi-V-I in the key of F major. The Dm11 and the melody remain unchanged but the function of the chord has changed. Dm11 now belongs to F major as the vi chord, so we would harmonise it with D Aeolian instead.

Here are the two harmonisations of each version:

Notice that the context and function of the chord changes how we harmonise it. The third beat is a G7 in the key of C, but a Gm7 in the key of F. It’s important for big band arranging to always know where each chord is coming from when working with functional music to make sure melodies are harmonised according to the key of the moment.

Chord-Scales 3

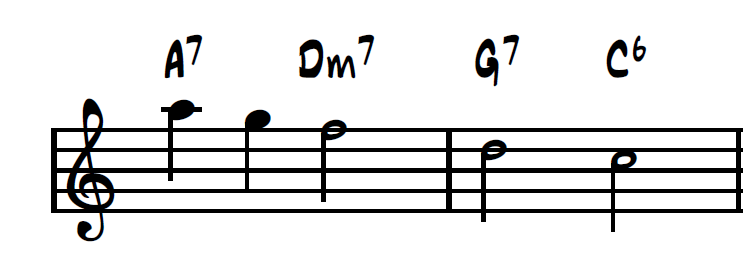

The final use for chord-scales becomes apparent when using substitutions. Let's take the ii-V-I in C from above, and add a secondary dominant to the ii chord. We get rhythm changes but starting on the VI chord instead of I:

We know how to harmonise melodies in this ii-V-I. All of these chords are diatonic to C so we simply use the chord-scale of C major to harmonise them.

But how do we harmonise the A7? If we use the C major scale, we won’t end up with the C# we need. The A7 secondary dominant here is really in the key of Dm. We should ensure that all our possible notes will fit well with our momentary tonic of Dm. At this moment, the Dm7 is a tonic chord in the key of D minor and a ii chord in the key of C.

Here’s the final harmonisation:

Confused? I’m not a fan of this theory for a reason, but it comes up enough in jazz circles it’s worth mentioning. I feel a lot of what it tries to solve is obvious and just a complicated way of dealing with simple harmonisation. Harmonising should be easy, as long as you respect the key of the moment and the function of the chord. Sometimes though it’s beneficial to work these things out methodically, especially when dealing with which available tensions to use.

MODES

All the music we’ve talked about so far has been functional i.e. chords that have a tendency to resolve in certain ways because of intervallic relationships. A lot of jazz is non-functional and is instead just a series of cool-sounding chords that bear little or no relationship to each other. This is often the case in modal jazz.

Modes are built from a parent scale, such as the major scale, but are better thought of as scales in their own right. Knowing the unique properties and structure of each mode, rather than in relation to their parent scale, is the most useful way to understand them. Here are the 7 modes of the major scale and their unique structures:

These also can be used as chord-scales. Take the example from earlier; a Dm11 chord. In a modal, non-functional context, a performer may choose to improvise using Dorian, Aeolian or even Phrygian. Modal chord progressions are often more static than functional ones. There are also modes of the melodic and harmonic minor that are used frequently but these are enough to be getting on with for now.

FURTHER READING

This article was just a quick primer to get you up to speed before moving on to voicings. If you want to go more in depth, or if I explained things really badly, I’d recommend the following:

The Jazz Theory Book - Levine - All Topics Here

Jazzology - Rawlins & Eddine Bahha - Reharmonization - Chapter 8 p.99

Modern Jazz Voicings - Berklee Press - Chord-Scale Theory - Chapter 4 p.41