17 | The Rhythm Section (Part 1)

So far the rhythm section has been only alluded to and not spoken about directly. I haven’t gone into much detail about how to write for the section because they deserved an entire article of their own. Just as a brief reminder, a typical big band rhythm section consists of:

Guitar

Piano

Bass

Drums

It’s not uncommon for the guitar to be omitted and/or for percussion to be added to this lineup. Percussion, if it is added, are usually congas or vibraphone, but can potentially include the whole selection traditionally available. The piano, bass and drums are all vital components of the big band sound. For ranges and more general info, check out this article first. Before we look at each instrument in detail, let’s look at some common devices of all good rhythm parts. I’ve gone over general points about good and bad parts in this article here, but let’s focus specifically on the rhythm section.

SLASH NOTATION

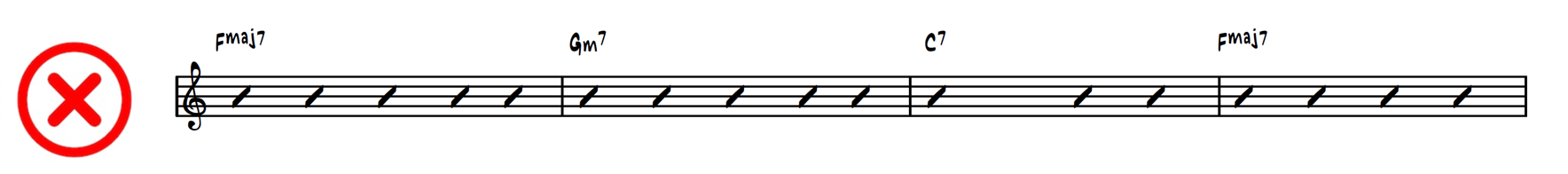

Slash notation allows the player to freely improvise their part, whether that be a solo or (more usually) an accompanying figure. There is always a slash per beat:

Just to remind you, there are three situations where we’d encounter slash notation:

Slash notation with chord symbols in a rhythm part. Without the word ‘solo’, this means an accompaniment part. Exactly what the musicians will play varies per instrument and style, but they’ll improvise and ‘comp’ (accompany) as a section under the horns.

Slash notation with chord symbols in a horn part. This means that there’s an option to take an improvised solo. Usually this section is repeated and two or more musicians will take a solo, usually decided in advance.

Slash notation on drum parts. This means the drummer will play ‘time’. Playing time means playing a beat/groove that fits the style and context.

You can use other instructions like ‘fill’, ‘light comping’, ‘solo’ etc. over slashes and the players will know what to do based on context. Be careful of using redundant markings though. In a fast swing chart, if a bass player gets slashes they’ll automatically walk - you don’t need to write it.

One thing you shouldn’t do is use more slashes than there are beats in the bar. Although when read at a glance, the player might not notice and play as normal, this still looks very confusing:

RHYTHM NOTATION

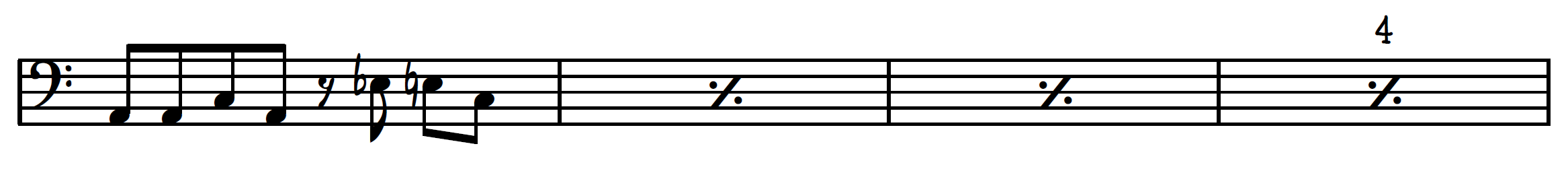

Rhythm notation involves slashes with stems. That way, the slashes can show a specific rhythm. It tells the player to very strictly play that rhythm and nothing else:

This is found in all rhythm parts and in parts for guitar, piano and bass comes with a chord symbol. The chords last until the next chord symbol appears. This allows the player to realise their own voicings but with a rhythm that the arranger gives them.

This type of notation comes up frequently in drum and percussion parts where the groove stops and the player is instructed to nail the hits.

When the rhythm is a half note or longer, a lot of notation software defaults to a diamond-shaped notehead. This might be a personal thing, but I’ve always thought it looks pretty terrible. I’d advise making the default a smaller triangle or using l.v. symbols as follows:

You can use a combination of slash, rhythmic and normal notation:

BAR REPEATS

Using these symbols, the arranger can show the player to repeat what was in the previous bar, two-bars or four-bars:

I have issues with this notation, when dealing with complex repeated riffs. Unless you’ve written a groove that the player has gone away, practised and learnt, sight-reading using these symbols is annoying. Sure, it saves space and printer ink but one of my pet peeves as a bassist is when someone writes a groove out for 2 bars and tells me to repeat it 15 times or something. This is annoying for two reasons:

I’m sight-reading: I haven’t memorised the groove I just played it 2 seconds ago so I often have to refer back to it. My eyes are therefore darting to what’s coming next while also reading the first two bars over and over (in extreme examples).

The chart loses visual structure. A sea of these repeat marks evens out the geography of the chart and when you’re looking at the first two bars over and over and then go back to try and find your place, the whole chart looks the same.

The takeaway from this is sometimes it’s better to just use standard notation over and over if the player is sight-reading. Then, you can use helpful bracketed numbers to show how many bars have passed, which is how the player will be counting.

The one place I will use bar repeats is if the groove is simple/easy to remember or if the player has time to learn it and wouldn’t be so reliant on the chart, it’s a different story and the clarity of the repeat notation might be beneficial.

Here this groove for electric bass involves a few jumps up and down the neck (like up to the F and then the following C) which would require looking away from the chart for a split second if the player isn’t already in the right position. The player needs to know where they are when they look back at the chart:

NOTE: I would only do this if the pattern is complex and is being sightread. Another viable option would be to have 2 bars written out, then a 2 bar repeat, 2 bars written out, 2 bar repeat etc.

CHORDS

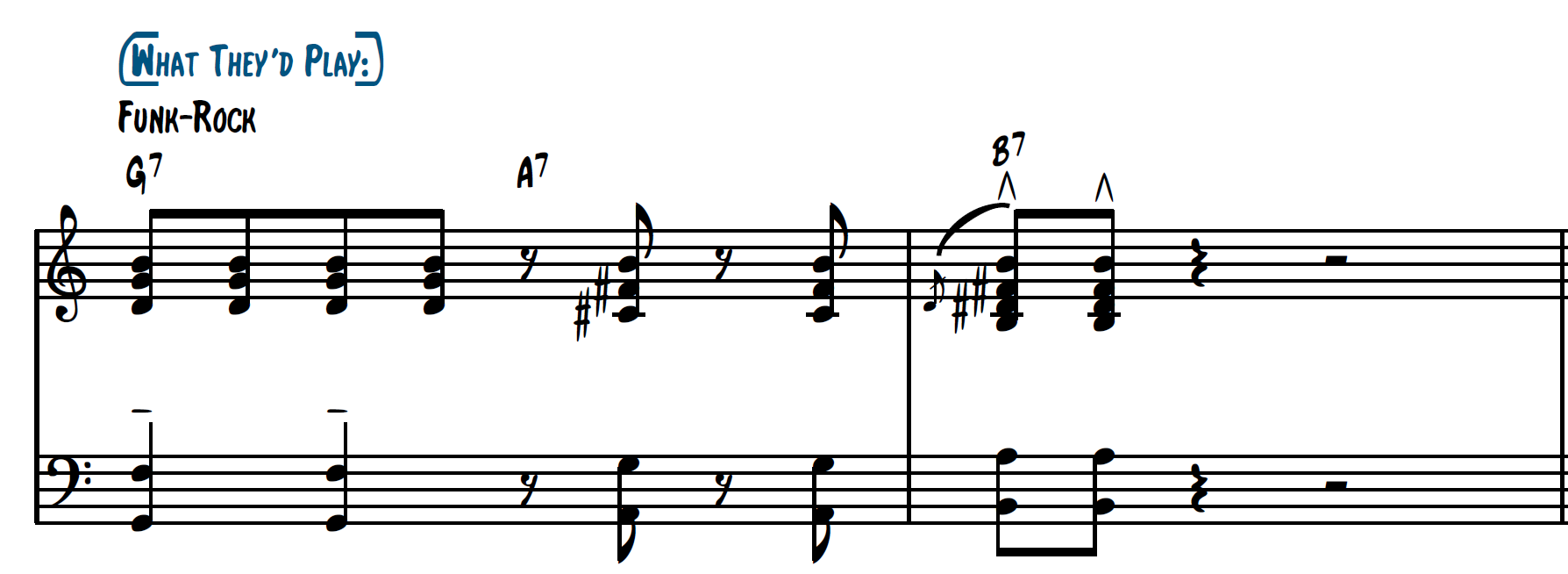

Keep the chord symbols simple. A rhythm player has to think about a lot and the more convoluted the chords, the more cumbersome the part is to read. Take a look at this simple ii V I and see which is easier to read:

The player will add the extensions of their own choosing so trust them to make colourful, artistically appropriate decisions. You’d get pretty much the same results giving the second option to a player and they’d be more thankful for it.

Having said all that, the exception to this is when you might give a rhythm section player a chord without enough information. In the G7 chord above for instance, if the horns had a #5 in their voicing, you should make the chord symbol specifically G+7 for the rhythm section. If you left it as just G7 the pianist, guitarist or bassist would play a natural 5 instead. This could result in some unintentional dissonances.

ARTICULATIONS

I’ve got a whole article on articulations used in jazz here, but didn’t mention much about the rhythm section. The trick with the rhythm section is to just use common sense. You want to match the horns with their phrasing, of course, but instruments in the rhythm section can’t make continuous sound like horns. A staccato on a choked crash cymbal is redundant, as is a crescendo through a held piano chord. These things slip through, especially when copying from the horn parts, but it’s worth going through the rhythm section parts to check for pointless hairpins and ineffectual articulation markings.

Now the general rhythm section notational things are covered, let's look at the instruments individually.

GUITAR

The guitar’s role in a big band is to provide harmonic support and thicken out the rhythm section texture. Usually this is done by playing chords, accompanying whatever is going on with the horns (‘comping’), or by supporting melodies. Occasionally, the guitar can be called on for a solo or to double lines for a specific colour. Guitars are great at establishing style. Playing funk, rock, jazz, latin etc. all require not only different playing styles, but also different tones and effects. Certain effects are so inherently linked to a specific genre that the guitar can be great at setting the tone of an arrangement.

Usually, an electric guitar is used with an amplifier. Acoustic guitars are very rarely used, and even then probably only for special effect. The style of guitar, the wood it’s made from, string choice and amp among other things all influence the guitarist’s tone. A guitarist in a big band will most often use an archtop guitar which is electric, but has a hollow body like an acoustic guitar. Note that semi-hollow and solid body electric guitars are also sometimes used. Solid body guitars are far more common in other genres such as pop and rock. This decision of which guitar and which set-up to use will always be down to the guitarist.

Notation

In a big band, guitar notation comes in a few varieties:

Chords with slash notation

Rhythm notation with chords

Single line melodies

Written out chords or harmonies

Chords With Slash Notation

The first is the most common and involves chords above slashes.

The guitarist will accompany the band in a stylistically appropriate way, helping to fill out the harmony. A good guitarist won’t get in the way of the piano or bass. Often they’ll play the upper extensions of chords while the piano has a voicing with the guide tones and the bass plays the root. Chord symbols need to be simple enough to be read on the fly, especially when the changes are fast, but also contain enough information that if the guitarist decides to add extensions, they won’t conflict with what the horns are doing.

For chord symbols, only use text. Never use the fretboard diagrams. It takes up so much room and a big band guitarist will know how to play their instrument. If you have to include chord diagrams, maybe for educational reasons, include it on a separate sheet with all the voicings the player might need for that chart.

As an example, if a guitarist sees this, they might end up playing something as follows:

2. Rhythm Notation With Chords

The second type of notation is rhythm notation. This is always accompanied by a chord. Each chord symbol lasts until it’s changed. Again, here’s an example of what a guitarist would see and then what they might play.

3. Single Line Melodies

As the third notation option, single line melodies are also very common which would be played exactly as written:

They tend to get drowned out in a full texture but can add colour to more sparsely scored lines. Nearly all melodic figures that would be played by horns are idiomatic to the guitar. These can also be played in octaves, but not as fast as single melodies, or in variations of most intervals - just be careful of consecutive minor/major 2nds.

Be wary of switching between melodic lines and chords. Guitarists can do it very quickly once they’re in the right position, but switching between chord stabs and a melodic like like a piano might would sometimes be better as one long melodic line with the guitar playing the top of the chord instead:

4. Written Out Chords & Harmonies

The final option for notation is to write out specific chords or voicings. This is not advised. A guitar does not voice chords like a piano. It’s often best to leave the exact voicing to the guitarist unless you’re one yourself, and even then, seeing a part cluttered with specific jazz voicings is not always very helpful. However, writing out a groove or riff or melodic line is common and perfectly fine.

Sometimes, you’ll want a specific note on top of the chord and I’ve seen all crazy kinds of notation to try and accommodate this, including a hybrid notation of small noteheads and rhythm slashes. To be honest, unconventional notation just raises more questions than it solves. The truth is the upper note of the guitar or piano is going to have such little effect on most situations while the horns are playing that you might as well just give rhythm notation or slashes with chords and leave it to their common sense and experience.

If it’s exposed and the top voice or overall chord voicing does matter and needs to be specific, it’s probably a feature, solo or groove that you can write out in notation and the player would look at beforehand.

It’s nearly always better to use rhythm notation for chords:

Upper Structures

Guitarists will often omit the root of the chord. The bass has it, and the piano might have it too if they’re also playing a rootless voicing. Instead, guitarists will play ‘upper structures’ meaning they’ll play the available tensions of a chord. If they see a D7 for instance, they might play an Am7 triad. This is the same as playing the 5th, 7th, 9th, and 11th of the chord. This way they stay out of the way of the piano while colouring and reinforcing the harmony.

You don’t need to do anything as the arranger to make this happen, but don’t try and force it. Giving the piano a D7 and the guitarist an Am7 chord symbol would be confusing and cause a lot of headaches. Give them both a D7 and the guitarist will choose their voicings.

In polychords, the guitarist should be given the whole chord so they can make an informed decision about their voicing - don’t just give them the top chord even though that’s what they’ll probably play.

In slash chords, where the bass is doing something specific, again give the guitarist the full information so they can make an informed decision about their voicings. They’ll leave the bass note to the bass or piano nearly every time, but they need to have all the information.

Articulations

All articulations found in this article here are possible on guitar. There are also a few more guitar-specific ones I’m not going to dive too deeply into here.

One tip I will give though is just be aware of the slur marking. This indicates that more than one note should be played in one pick stroke (called hammer-ons and pull-offs). Any more than two notes, or up to four in fast scale-like passages, can lose volume very rapidly. Long slurs make no sense to a guitarist:

If you’re unsure it’s best to leave them out all together. In fact, as most things are alternate picked, you’d be safer.

One other guitar-specific articulation the arranger has is palm muting. With the right hand, the player dampens the string by the bridge and creates a muffled effect, effective when used in conjunction with effects like overdrive or distortion. A line should be used with ‘p.m’ to show this:

Tuning

The guitar in a big band is by default in standard tuning. Other tunings on guitar are available - some are more common in other genres and some are more idiomatic to acoustic guitar. Some common variants include: half a step down (Eb Ab Db Gb Bb Eb); D A D G A D (pronounced ‘dad-gad) for acoustic guitar; and drop tunings like drop D (D A D G B E).

If you were to tune to something other than standard, specify it at the beginning of the guitar part very largely because it’s so uncommon. For instance, write ‘Eb standard’ in a box.

These are all very uncommon in big band writing and you shouldn’t really use them because it messes with notation too. I won’t get into too much detail here, but DADGAD for instance would change the position of every single chord using the lowest string and create a lot of work for a guitarist used to reading standard notation. There’s also no universal system of notation for the things like Eb standard where the guitar effectively becomes a transposing instrument. It’s just a headache.

I felt the need to mention it as it’s so common in other genres and in pit playing, but for a big band it really shouldn’t be thought of as a viable option unless it’s a guitar feature for a specific player.

Effects

The range of effects available to the guitar outmatch any other instrument in the big band. The tone can be altered in a lot of different ways. By default in a big band, the guitarist will play ‘clean’ and no indication of this is needed unless it’s not obvious (if you write ‘big rock solo’ with no FX indication, you’ll get a question because they wouldn’t usually play it clean).

Overdrive and distortion introduce a dirtier, more aggressive sound found in rock charts. Wah, phaser and flangers are often the sound of funk. A guitarist will be able to activate these effects at the press of a pedal but not all big band guitarists will bring a pedalboard unless they know they need to.

I like indicating my effects settings in boxes above the stave:

Guitar Part Layout

Finally, here’s an example of a guitar part from one of my charts incorporating everything mentioned above:

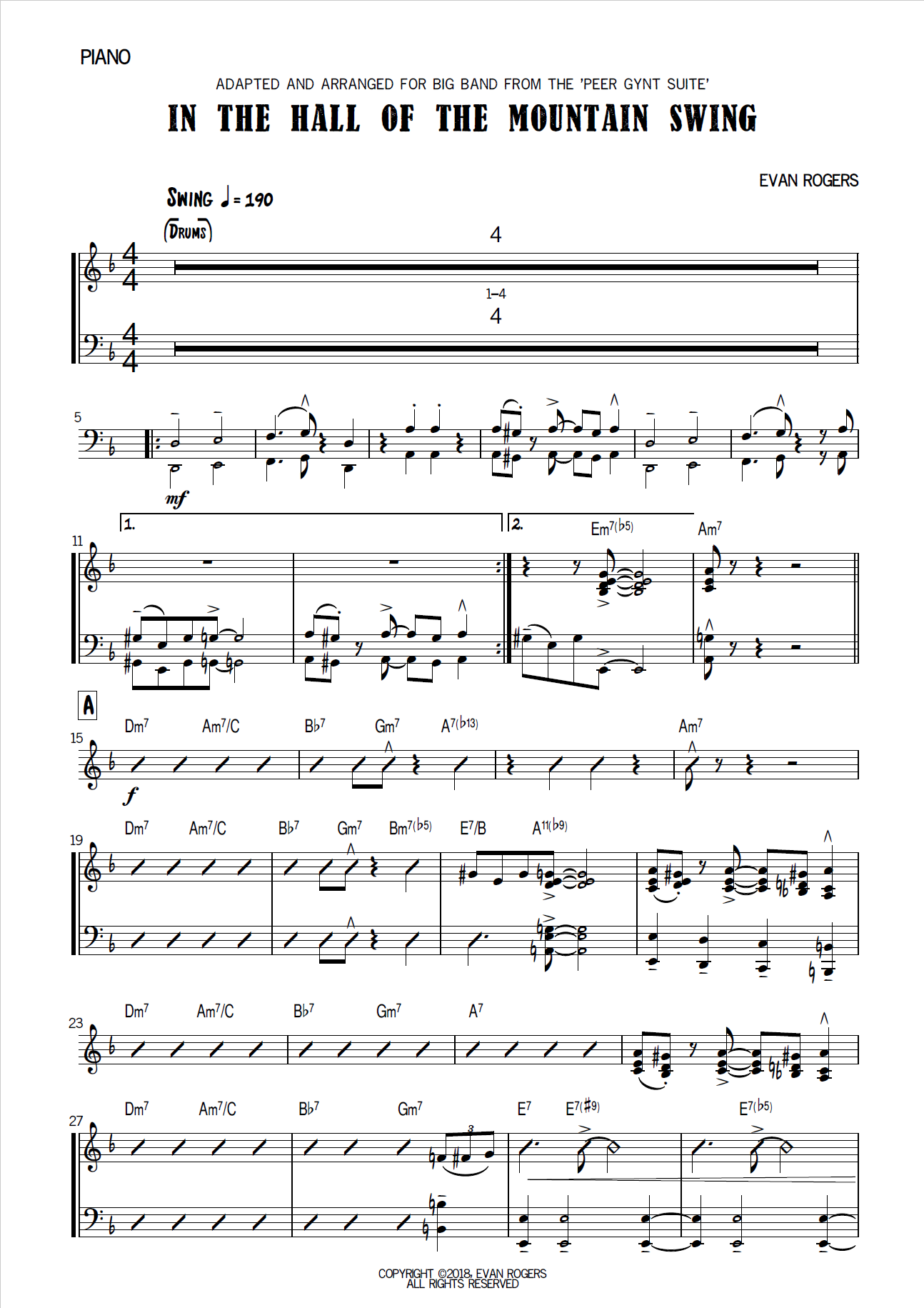

PIANO

The piano is a staple of nearly every form of jazz. The pianist holds down the harmony, fills out extra space in the texture, provides fills, takes solos and generally glues the sound of the rhythm section and horns together. Pianos are traditionally acoustic (or are at least keyboards with an acoustic grand sound) but electric pianos, organs, synths and unfortunately the occasional keytar aren’t uncommon. For most arrangers and composers, the range is pretty self explanatory as is the playing technique. 8va and 8vb symbols are standard.

Notation

The piano in a big band uses the grand staff (treble and bass staves) but is often condensed down to just one stave to save space, especially when comping. Here are the following types of notation acceptable to give a big band pianist:

Chords With Slash Notation

Rhythm Notation With Chords

Written Out Melodies & Chords

Like all the rhythm instruments, using all notation methods interchangeable, even within a beat of each other is fairly standard.

Chords With Slash Notation

This is very common, there’s no need to write the word ‘comp’ or anything. The pianist will automatically support the band in a stylistically appropriate way. Like the guitar, the chords should not be overly complex, but give a complete view of the harmony while allowing room for freedom. It’s also possible to have the right hand comp with slashes, and the left hand play a written line or vice versa.

It’s common to reduce the 2 piano staves into 1 for this kind of notation to save space on a part.

2. Rhythm Notation With Chords

Again, similar to the guitar, the pianist can focus solely on rhythm while voicing their own chords. The only thing to note here is that the top note isn’t always clear to the player and their voicing might go too high or too low with respect to the horns. To get around this, you can give just the top note and also slash notation, but this can be messy. I prefer to leave it to them to hear or use option three below.

3. Written Out Melodies & Chords

Unlike the guitar, writing out lines and chords for the piano is not so problematic. As long as they don’t exceed more than 10 notes and the range of each hand is comfortable (about an octave to be safe) you can’t go too far wrong. Moving quickly between complex chords can be difficult though so leave things like 4-note chord 16th notes out.

The only other word of caution here is that a pianist will often voice chords better than you, unless you’re a jazz pianist too, so it’s best to leave it to them. There are also standard voicings for certain contexts and you could risk losing the trust of the pianist if you start to contradict decades of jazz piano playing.

The main benefit that comes from writing out the voicing yourself is that you can control the piano’s place within the texture. You have control of the exact voicing and range of notes or can indicate a specific groove or melody to be played. Notice the stems down for the right hand and stems up for left hand when the notes share stave:

The most common kind of piano part for big band charts is a mixture of all three techniques. Melodies are notated and rhythm notation for nearly all chords while slash notation indicates general comping. See the part below for an example.

Articulation

The piano is capable of most articulations that the horns are, but just be aware that the piano is fundamentally a percussion instrument. The nuances of a tenuto, bend, shake or scoop are not idiomatic to the piano. Some of the other jazz-specific articulations like falls don’t translate amazingly well but are still somewhat possible. Indicating them shows your intention to the player or what the horns are doing so aren’t always wasted ink.

The pianist in a big band will not use the sustain pedal. Unless in a ballad, or for effect, ‘ped.’ markings shouldn’t be used.

Piano Part Layout

Like before, here’s a piano part incorporating everything discussed so far.